Chester began life as Deva Victrix, a Roman military base, in AD48. The fort built here is larger than any of those built at this time, which has suggested to some folks that it may have been Chester, and not London, that was intended as the capital for the province of Britannia Superior. Roman remains abound in Chester, with several streets following the Roman layout.

^ the above two photos show the Roman Gardens, designed in the 1930s on what was the Roman bath house.

The odd survival from the Roman fort includes the Strong Room (aerarium), where the strongboxes that housed the army paychests were kept (contrary to popular belief, Roman soldiers were only partially paid in salt). The room directly above this was where the standards were kept, the sacellum. Hence the standards in the photo:

The south-east angle tower of the fort has also survived:

In addition to the fort, an amphitheatre was built just outside the Roman walls, across the road from the above tower. Today, only about two-fifths of the amphitheatre can be seen, as the rest was built over before it was discovered. But it still remains the largest amphitheatre in Britain.

^ during excavations - this area has now been consolidated, as can be seen in the first amphitheatre picture.

^ after the excavations.

The Romans didn't use the amphitheatre for long at first, with it becoming a rubbish dump when the Legion moved north to help build Hadrian's Wall. It was finally abandoned in AD350. The amphitheatre lapsed back into being a quarry and a dump during the middle ages, and it is possible part was used as a crypt for the nearby St John's Church, until it was eventually uncovered in the 1950s.

The Church of St John the Baptist, then. This is the city's oldest church, and was the first cathedral (more on this later). It was constructed in 1075 when the Bishop of Lichfield moved the diocese to Chester, but he couldn't have been that happy here as he moved on again in 1102 to Coventry.

In the 14th century, it was extensively remodelled, with a complex of chapels was added onto the east end. However, these chapels were soon neglected and, following the dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s, when the church was refounded as a parish church, these chapels were walled off and allowed to collapse into ruin.

Today, the maze of arches looks like something from a Caspar David Friedrich painting - you can almost see the mist swirling through the ruins... well, almost!

Nearby is a small anchorite cell, which local legend says was the home to King Harold, who miraculously recovered and fled to Chester following the Battle of Hastings.

Much of the built heritage to be seen in Chester today starts with the medieval city. The Castle at Chester was built in 1070 on the orders of William the Conqueror, and became the seat of the Earldom of Chester. Domesday Book makes a record of what the laws were within the city before the conquest, which is an interesting read. At the time of the Conquest, there were reckoned to be 431 houses paying geld (land-tax), but when the city was given to William's nephew Hugh d'Avranches in 1071 there were 205 fewer houses. Given that Chester was one of the last places to fall in the Conquest, it seems the city saw some violent fighting.

Chester Castle today is a ruin of its former self. The law courts have taken over the outer bailey, and the Georgian mansion Napier House (behind the wall in the right of the above picture) forms the main part of the inner bailey. There are, however, some interesting medieval bits left.

The Agricola Tower, named after the Roman governor of the province, is the most impressive. On the second floor is the chapel of St Mary de Castro, formerly used as a gunpowder store.

Originally a timber construction, it was rebuilt in stone by Earl Ranulf, the third earl. Henry III greatly remodelled it when it passed into royal hands, and the castle was used as a staging base during his son Edward I's Conquest of Wales, and in the Civil War it was garrisoned for the Royalists (more later). During the Great Recoinage of 1696-8, Chester Castle was the site of one of only two mints in the country (the other being in London). "Clipping" coins was a practice going on for centuries. Back in the day, a coin would be made of actual gold or silver, depending on the denomination, and its value determined by its weight. Clipping off the edges to get slivers of silver or gold to then re-use took place, often greatly devaluing the coin, so in the late 17th century it was decided to withdraw all coins from circulation and replace them with coins with marked edges, the theory being you couldn't clip anything off. It actually proved to be a disaster when William III had to withdraw his army from the War of the Grand Alliance (a European coalition against Louis XIV of France, aimed at curtailing French expansion) because he couldn't afford to pay them. The mint at Chester was presided over by Edmund Halley, of Halley's Comet fame, and Isaac Newton was in charge of the London mint.

Back to the Normans, now. Earl Hugh, known by his epithets as Hugh Lupus (the Wolf) or Hugh the Fat, was one of the great barons of Norman England. He earned the nickname Lupus because of his savage ferocity against the Welsh. Chester, along with Shrewsbury and Hereford, was created primarily as a bastion of strength to contain the Welsh after the Conquest, and collectively they became known as the Welsh March. In this border country, King William effectively delegated his power to the three Marcher Lords, giving them palatine powers over their lands. Nowhere else in England did any man other than the king have the power of life and death over other men.

Earl Hugh provides the segue into the next subject: Chester Cathedral. Originally founded as a small timber building in about 660, the church was built by Werburgh, the daughter of the Mercian king Wulfhere, before she left to be a nun at Ely Abbey. Wulfhere recalled her to Chester to become an abbess at the church here and performed many miracles, such as restoring to life a goose that had been killed and eaten. When she died, she was buried at the church, which was subsequently remodelled to provide a more fitting tomb, during which building work her corpse was discovered to be still fresh, which led to her canonization as a saint. The monastery was founded in the ninth century, and in 1092 a Benedictine Abbey was founded on the site, dedicated to St Werburgh.

The Abbey was founded on the orders of Hugh d'Avranches, with the first Benedictine monks coming from the abbey at Bec, one of the wealthiest and most influential abbeys of the time.

^ the 13th century Abbey gate.

As with many abbeys, Chester was rebuilt almost constantly during its history, becoming ever more grand each time, and building work was being carried out right up to the point the abbey was dissolved in 1539, meaning the ceiling had to be finished in timber rather than the planned stone vault.

^ the crossing tower.

^ the rood screen.

Following the dissolution, the Benedictine Abbey was re-consecrated as Chester Cathedral in 1541, forming the centre of one of the six new English bishoprics. During the Civil War, the cathedral stained glass was replaced with plain, stained glass making an eventual return to the cathedral in 1835.

The West Window, above, was replaced in 1961 following bomb damage during World War Two.

^ the cloister garden.

^ the chapter house arcade.

The Cathedral was repaired and refurbished during the Victorian era by the noted church restorer Sir George Gilbert Scott, and it was at this time the chapter house window was installed:

^ the chapter house vestibule.

Just opposite the Cathedral is the former Church of St Nicholas, built in about 1300 because the citizens of Chester apparently had the right to use the South Transept of the Abbey Church for their parish church. The Abbot wasn't keen, so built this, but at the dissolution it was closed. After that, it was variously as a Wool Hall, a Theatre, a Music Hall and a cinema, until now it's in use as a shop.

Chester is famous for its unique two-tiered shopping experience, the Rows. The origin of these shops is somewhat unclear, but they presumably date back to the 13th century. Shop design in cities at the time was largely of an undercroft used as the shop and warehouse, with the private hall built above. Because of the bedrock, cellars could not be built underground so were instead built at street level, and over time these cellars became shops with the halls above converted into more shops, resulting in the two-tier experience. Possibly the earliest shop front in the country exists on Bridge Street, and shows how this arrangement may have worked:

Chester is famous for its unique two-tiered shopping experience, the Rows. The origin of these shops is somewhat unclear, but they presumably date back to the 13th century. Shop design in cities at the time was largely of an undercroft used as the shop and warehouse, with the private hall built above. Because of the bedrock, cellars could not be built underground so were instead built at street level, and over time these cellars became shops with the halls above converted into more shops, resulting in the two-tier experience. Possibly the earliest shop front in the country exists on Bridge Street, and shows how this arrangement may have worked:

^ the Blue Bell, centre, is apparently the oldest intact medieval residence in the city.

Another remnant of medieval Chester is the Old Dee Bridge, once the only crossing of the Dee into Wales. Built in stone in 1387 to replace the old timber (and a former Roman) bridge, it connects Chester to Handbridge, once an important Norman fishing collective.

Handbridge is actually a very important place. Not only does it contain the only remaining rock-cut Roman shrine still in-situ, it was also the site of a Saxon palace on what is now Edgar's Field. The great-grandson of Alfred the Great, Edgar stayed here in 973 to attend a ceremony at what is now St John's Church. At this ceremony, six other kings apparently swore their allegiance to him, making Edgar the very first King of England in the modern sense. Edgar's two sons followed him as King of England, Edward the Martyr and Ethelred the Unready.

^ the Minerva Shrine in Edgar's Field.

Most of Chester abounds in half-timbered structures, such as Stanley Palace, built in 1591:

Chester remains, however, a very confusing place. You could be forgiven for thinking it is full of Tudor remains such as this, but the Black-and-White Revival of Victorian England has confused matters tremendously, as old buildings were "restored", and new buildings created to look old. So let's have a look at what we're dealing with here... Stanley Palace is an original. God's Providence House, which was the only house to escape the outbreak of plague that swept the city in 1647, is a Victorian restoration:

King's House, a former art gallery, was built in the Victorian period. The statue of Charles I in the central recess had to have its legs cut off in order to fit there:

St Michael's Buildings, one of the entrances to the Grosvenor shopping centre, is post-Victorian, being built in the Edwardian era:

The Falcon pub is an original, though has gone through so many restorations it's hard to tell anymore:

73 Northgate, now a restaurant, started life - unbelievably - as an Edwardian fire station:

See what I mean about it being confusing?

See what I mean about it being confusing?

King's House brings me on to the next big event, the Civil War. Cheshire declared for the King at this time, and remained staunchly loyal. In 1645 Charles arrived in the city personally, shortly before the Battle of Rowton Heath. He is supposed to have watched the retreating Royalist troops return under fire to the city from the King Charles Tower:

^ the memorial to the Battle in Rowton village, just outside the city.

Further connections arise at Gamul House on Lower Bridge Street, where the King stayed at the town house of the Gamul family after the battle:

Further connections arise at Gamul House on Lower Bridge Street, where the King stayed at the town house of the Gamul family after the battle:

^ Gamul House is the one in the middle, with the oval windows.

Having refused to surrender nine times previously, the city surrendered in 1646.

The Cross was knocked down in the Interregnum, with pieces hidden over the city by Royalists to prevent their destruction. It was restored in 1975, but the statuettes from the lantern are still missing.

The Cross was knocked down in the Interregnum, with pieces hidden over the city by Royalists to prevent their destruction. It was restored in 1975, but the statuettes from the lantern are still missing.

So far, I've neglected to mention a fairly important part of Chester - the Roodee Racecourse. Chester has the distinction of having the oldest racecourse still in use, the first race taking place in 1539. The site of the course was once the Roman quayside, when the River Dee was still navigable. The name Roodee is connected to the cross, or rood (remember the rood screen in the Cathedral?), the stump of which can be seen just off-centre in the picture below:

^ the trees at the rear of the racecourse mask Curzon Park, the extremely affluent area established in the 1840s when rich merchants from Liverpool decided to live here. The advent of the railways, which can be seen to the rear-right of the picture, made it very popular with commuters.

The races were particularly popular during the Georgian era, when the fashionable gents would bet on the cock fights in the cockpit (where the Roman Gardens now flourish) before toddling off along the waterfront to the racecourse to bet on the horse races. It was the Georgians who re-consolidated the city walls from the rougher medieval circuit, providing an elegant promenade to tour the city or the waterfront.

^ the bridge to the left in this picture is the Old Dee Bridge, once the only bridge connecting Chester with Wales.

^ the promenade along the riverfront, looking towards the suspension bridge.

The Bluecoat School (above) is just beyond the Northgate, and the site of the city gaol, with cells infamously known as "Dead Man's Room", "Snake Pit" and "Chamber of Little Ease". The conditions were shocking within this prison, and it was demolished in 1808. The prison has gone, but the 'bridge of sighs' remains - the original bridge of sighs, in Venice, was so-named because of the sighs of the condemned prisoners traversing it, though now the expression conjures up mooning lovers in Oxford.

The bridge leads us wonderfully into the canal, another huge part of Chester's success. Work on the canal began in 1772, with an effort to link the Trent & Mersey Canal at Middlewich with the River Dee, a move that would enable salt mined near Northwich to be moved much more easily. For those who don't know, Cheshire is replete with saltflats, which is what made the area so valuable to the Romans, and why Cheshire cheese is so crumbly. The venture was never finished, and with the Ellesmere Canal opening in 1805, was largely unnecessary, anyway. In 1825, the Birmingham & Liverpool Junction Canal was authorised, with Chester providing an essential link. Liverpool being the hugely important trade centre that it was, Chester was suddenly a lot more important than ever before, providing an essential link between Birmingham, Stoke-on-Trent, Manchester, and Liverpool. This venture was so profitable that in 1846 the Shropshire Union Railway and Canal Company was formed from the Birmingham & Liverpool Junction Canal.

Industry grew up along the canalside during this period, including the Leadworks:

The chimney you see here is 167ft tall, the tallest building in Chester. It's what's called a Shot Tower, used in the manufacture of lead shot. Now, a word about balls. In the 17th century, lead musketballs were not truly spherical, and imperfections on the surface often led to their disintegration both upon leaving the barrel and whilst still inside. In 1783, it was here at Chester that a chap called William Watts perfected the manufacture of spherical shot, which was subsequently used in the Napoleonic Wars to great effect. Basically, by pouring a mixture of molten lead and arsenic from the top of the tower, through a griddle into a vat of water at the bottom, the lead will form into globules (stop me if I get too technical here!) on the journey down and, upon entering the water, form truly spherical shot.

The Steam Mill a little further down the canal (above) once housed one of the first ten of Boulton and Watt's steam engines.

^ Telford's Warehouse, with the "shipping holes" for unloading cargo. Possibly not built by Thomas Telford.

Returning to the Walls from the Canal here, we arrive at the Water Tower Gardens. Back in the day, when the Dee was still navigable, the river used to run right around the walls. As silting up gradually changed the course of the river, a spur was added to the wall in 1322 with the Water Tower built at the end to defend it. The silting up continued, however, and the area is now completely dry. The tower you can see to the right amid all the trees is Bonewaldesthorne's Tower, which itself was originally stood in the river.

It was during the Victorian era that Chester as we see it today really took shape. The Grosvenor Bridge, opened in 1832 by Princess Victoria, spans the Dee at 200ft and was, at the time, the longest single-span bridge in Europe.

I've already mentioned the Black-and-White Revival, of course, in which the Public Baths were also built between 1898-1901. The council built a new public baths at the Northgate Arena in the 1970s, deeming these unfit for competitive swimming.

The other major building the Victorians gave us here is the Gothic Revival Town Hall, apparently modelled on a French Chateau. Opened in 1869, it is crowned with a 157ft high tower, three sides of which have a clock on.

The side of the tower that faces Wales is left blank, which has led to the assumption of Chester "not giving Wales the time of day" - an anti-gallicism that links with the law that allows any Englishman to shoot a Welshman caught within the city walls at night, provided he does so with a crossbow. While it is still apparently enshrined in law, it is not a legal defence for murder.

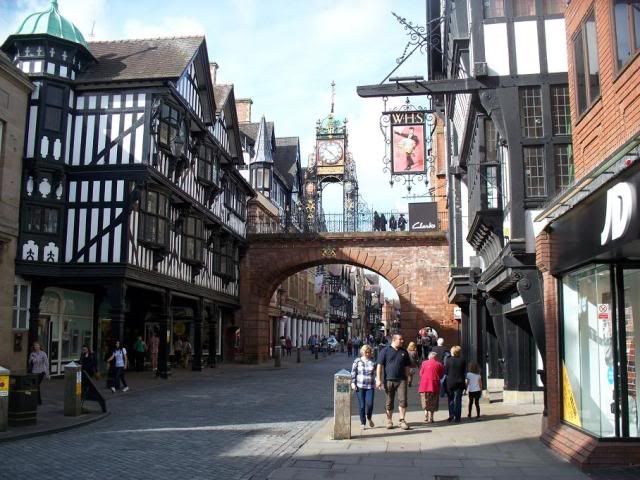

Perhaps more than any other structure within Chester, the Eastgate Clock is the most famous:

Installed in celebration of Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee, which took place in 1896, the clock was constructed in 1897 and not unveiled until 1899, on the Queen's 80th birthday. It is said to be the second most-photographed clock in England, after the Clock Tower on the Houses of Parliament.

And so we come to the end of this trek around Chester! I do hope you've enjoyed it as much as I have. No blog can replace the experience of being there, of course, so I highly recommend a visit to all and sundry!

No comments:

Post a Comment